News

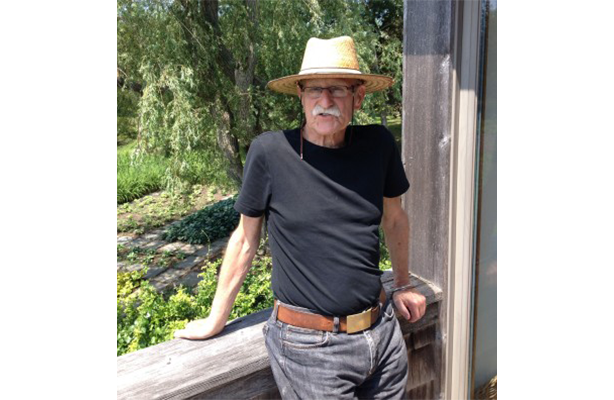

In Memoriam: M. Paul Friedberg

The Spitzer School of Architecture mourns the loss of former faculty member M. Paul Friedberg, the founder of the undergraduate program in urban landscape architecture in 1970.

Here are excerpts from “Remembering M. Paul Friedberg” by Charles A. Birnbaum for The Cultural Landscape Foundation:

Maverick, innovator, fearless … these are just a few of the words that begin to characterize M. Paul Friedberg, the pioneering landscape architect who passed away on February 15, 2025, at age 93.

He was serious about the idea of child’s play and an unrepentant believer in the virtue of cities when U.S. cities were at their nadir. He worked mostly in the public realm, which meant that everyone was his client; he knew he was responsible both to them and for them. That challenge and joy of creating places for people, and the energy that people brought to public places, continually motivated Friedberg over a career that lasted more than six decades.

Friedberg however would be an active and at times confrontational maverick on a quest to change that – as a landscape architect, architect, planner, artist, educator, author, urbanist, outdoor furniture-designer, and all around provocateur, Friedberg would push the envelope on what a landscape architect was (e.g. the lead planner – think big), what they did (e.g. reclaim the city), and what they looked like (e.g. actively courting and employing women and minorities in his practice and at the City College program).

In the footsteps of great landscape architects, including the Olmsteds (all three), and Gilmore Clarke and Michael Rapuano (enabled by Robert Moses), Friedberg came along when New York City and many others were in decline and many landscape architects had turned to the suburbs. Complaining that there was more than “drawing tennis courts and parking lots for engineers,” Friedberg recounted in a 2006 interview with The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) for a Pioneers Oral History that “I’m one of the few who accepted the city as a viable place to work, and to enjoy the diversity and the places that are created for people to come together, understand each other, through the joy of sharing. If there’s anything, it’s that. It’s enjoying the city, removing the landscape architecture bias of the past the preconceived notion that the city is a hostile place. And, to me the city is where we are, the salvation. If you’re going to preserve the larger landscape, the city is the only way. Density is the only way. That’s it.”

It has been 60 years since Friedberg unveiled his radical solution for the problem of public housing in New York City – Jacob Riis Plaza (1965). This revolutionary approach, enabled by the Astor Foundation, launched Friedberg’s unique approach to what he called – the “total play environment” – a carefully choreographed series of simple, sculptural landscape vignettes that included a tree house, mounds, and a tunnel – all allowing for, and encouraging physical, emotional and sensory exercise and participation. Peter Walker, recipient of the 2004 American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) Medal (the same year that Friedberg received the ASLA Design Medal), has stated that “modern urban landscape design” began with Friedberg’s Jacob Riis Plaza, and “like Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion it was unlike anything seen before in the modern city.”

National and international accolades followed its opening (including in the New York Times and Life magazine). For the 34-year-old Friedberg, this was a watershed event. In the more than half century that followed, with his work in the U.S., Canada, India, Israel, and Japan, Friedberg not only redefined the role and scope of the landscape architect but the design vocabulary employed, stylistic approach (embracing both Modernism and Postmodernism), and landscape typologies (blurring the lines between the landscape architect and the artist). His seminal works include the first “park plaza” with Peavey Plaza (1975), and the innovative Loring Greenway (1974), both in Minneapolis, MN; mixed use waterfront revitalizations (e.g. Battery Park City, 1988; The Yards, Washington, D.C., 2011); multi-use plazas (Pershing Park, Washington, D.C., 1981); rooftop plazas (Fordham University, N.Y.C., 1999), regional parks (Holon Park, Israel, 2000) and myriad civic spaces (Olympic Plaza, Calgary, Canada, 1987, Aroma Square, Tokyo, Japan, 2000).

In addition to those landscape architecture commissions where he challenged acceptable conventions, Friedberg’s constant pursuit of innovation and creativity in the making and crafting of children’s play spaces has been a constant in his career (e.g. Carver Houses in N.Y.C., 1963, East 67th Street Playground in Central Park, N.Y.C, 1985, and, Yerba Buena Gardens in San Francisco, 1998), as has been his quest to expand the profession as an educator.

Paul Friedberg is survived by his wife, Dorit Shahar, and their daughter Maya, and by his sons Mark and Jeffrey from his marriage to his first wife, Esther, who passed away in 1982. He is also survived by an extraordinary body of work that continues to enliven cities, enrich those who interact with his landscapes, and to inspire landscape architects to create.

Learn more about M. Paul Friedberg’s legacy by visiting The New York Times.